Compensation, Diversity,Equity,Inclusion, and Justice, Work/Life Balance

We must take a hard look at compensation, re-imagining work/life balance, and removing gender and other biases in our field to better motivate and value our Jewish community professionals today and strengthen our organizational culture and deliverables that will enhance our collective mission: to strengthen Jewish life.

This blessing highlights three areas in which we can make some adjustments. We take a hard look at compensation, how we can re-imagine work/life balance, and how we can remove gender and other biases in our field. If we, collectively, make at least some of the necessary adjustments, we will better motivate and value our Jewish professionals. This will ultimately lead to stronger organizations tomorrow that can more successfully accomplish their missions.

ADJUSTING OUR COMPENSATION PRACTICES:

The Leading Places to Work studies have revealed that, among a fairly representative sample of Jewish communal service professionals, 47% feel they are not compensated fairly. Why is that? Our narratives have provided for us the following insights:

- Lack of Transparency – We lack a culture of transparency around salary rationale. Often there is a lack of sufficient data to understand how different salaries compare. While this is slowly changing, it is still a norm rather than the exception that organizations do not post the salary range when advertising, presumably in order to hold leverage in a forthcoming salary negotiation with the desired candidate. Further, within an organization, folks can only guess, unless they work in Human Resources or in a position of leadership where they become aware of staff salaries, what others make and if their salary or other benefits compares fairly. The only salaries an employee or anyone outside the organization might know publicly are the top 5 organizational salaries that are publicly found on the organizations form 990 tax return, which can be found on guidestar.org, or in The Forward’s annual survey of the Top 50 earning CEOs in our field.

Lack of Transparency creates a culture of guessing, not of blessing. It creates a culture of confusion, not a culture of fairness and feeling good about one’s compensation. Narrative after narrative has made it clear that Jewish community professionals do not need to make a very high salary to feel valued, but they do not want to feel stressed over their compensation, to have their perceived low compensation a de-motivator to an otherwise motivating job situation. They also want to be able to know that the organization takes their role seriously and is investing its own resources into their success.

It was unclear, for example, if Marc Fein’s employer is taking seriously those serving youth today, or if Rachel, whose camp is a major source of the JCC’s revenue, earns a salary that represents her essential role in the sustainability of the entire institution. It certainly is visible when the executive is paid well – David, Ezra, Aliza, and Becky among them – though, interestingly, Aliza and Becky worry if they are being underpaid and undervalued as a result of their gender, which can lower their motivations. Needless to say, a lack of transparency can lead to employees guessing and often perceiving they are being paid less than what they are worth, an enormous demotivating factor.

- A Culture of Mediocrity – In Blessing #7, we talked a lot about cutting the BS and the systems that prevent us from doing our best work and that frustrate our Jewish community professionals. One of these systems is the way we look at salaries and at raises. Many of our organizations indicate that they want to be fair to all of their employees. Executives and Boards of Directors often interpret this as either no or all employees getting a raise in a given year as a COLA, or cost of living adjustment increase. Further, everyone should get the same COLA, typically 2-3% per year. Many organizations follow the COLA adjustments the government makes to social security payments, which in 2018 was 2.8% according to the AARP.

Yet for Jewish community professionals who perceive themselves as or are told that they are high performers, this practice can feel very unfair. High performers must be recognized through an increase that isn’t the same as the employees whose work is deemed merely satisfactory. For us to implement such a practice in our organizations, we need to have a fair and robust performance review process and consider a hybrid COLA practice coupled with a pay-for-performance model in which employees receive additional salary increases related to their performance, which is more prevalent in industries such as healthcare where there are quantifiable deliverables. In the Jewish sector, deliverables can also be quantifiable as they relate to meeting fundraising goals, achieving high quality programs as measured by attendee surveys or testimonials, or simply exceeding one’s job expectations as determined by management in partnership with the professional, with supervisors recommending merit increases to those who have demonstrated exceptional work.

Again, compensation matters, not merely to pay the bills, and certainly not in an effort to get rich, but as a statement of how much the organization values their contributions and how each can feel recognized for their strong performance and dedication to the organization. Though non-profit professionals aren’t “in it for the money,” to give a blanket uniform increase to everyone also gives this message: “work hard or don’t work hard, and you’ll get the same reward.” This too can de-motivate our staff even though our intent may be the opposite.

Certainly, compensation is more than merely one’s annual or hourly salary, and a high performer can receive a myriad of benefits outside of an increase in base salary to feel valued for their work, including intriguing professional development, increased flexibility to do their work, more interesting projects, or access to learn from important leaders in the field, including their own executives. Yet, the paycheck still is an important marker, so we must make a statement that high performance and contributions are properly recognized in their bank accounts as well as elsewhere.

- Lack of Abundance Thinking – Naomi Korb-Weiss, formerly the Executive Director of PresenTense, North America, and currently a consultant to many Jewish not-for-profits, wrote a superb piece on ejewishphilanthropy.com several years ago that summed up our obsession with not investing too much in overhead expenses, quoting Dan Palotta. She includes staff salaries in her definition of overhead. The misguided thinking starts with the idea that donors want to have their donations applied directly to the program or the project, not to keeping the lights on or, often, to the people who are making the project come to life.

Similarly, the misguided thinking goes that if we give too much to investing in people, there won’t be enough funds for the program or other needed expenses. This is, again, an example of the zero-sum game thinking that is part of a scarcity, rather than an abundance, model of thinking. If programming wins, staff loses. If staff wins then programming doesn’t have enough funds to be successful, and that is not what the donors want to see in how their money is invested anyway. It is easy to locate an annual report that proudly demonstrates its 90% program/10% overhead ratio.

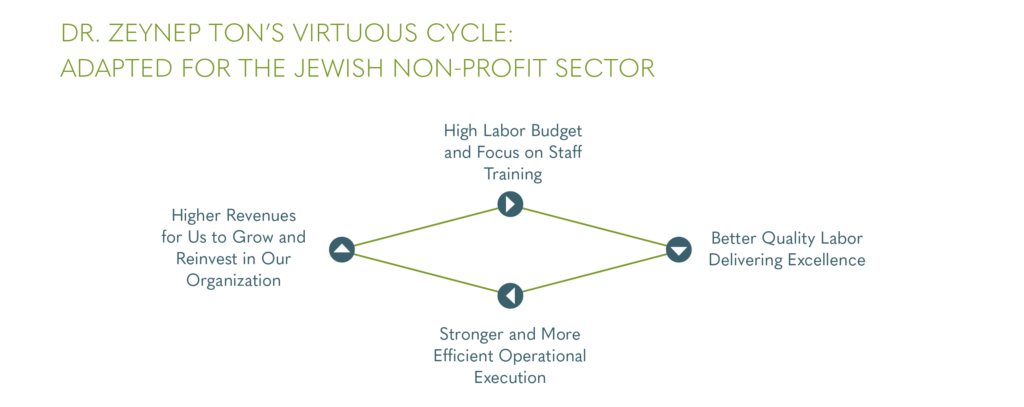

Sadly, this can leave Jewish community professionals today feeling that they are underpaid, undervalued, underinvested in, and under-appreciated. We have to remind ourselves of Dr. Zeynep Ton’s Virtuous Cycle, one that Palotta in his TED Talk aimed at not-for-profit organizations:

If we have higher labor costs, and we execute our operations well and cut the BS, we will have better operational execution and higher sales and profits. Yes, if we pay our staff MORE then we will make more both in the mission bottom line and the financial bottom line in return!

How to Adjust – Pay Well, Above the Market Rate

If we examine our profiles, those who feel they are paid really well, typically but not exclusively the male executives, feel valued by their pay check and don’t worry so much about their compensation. Those that feel they are not still give their one hundred percent, yet they take notice of it, which takes up energy and decreases their feeling of being valued. In the long term, this may impact their performance and precipitate an exit from our field altogether. For example, Marc feels his pay as a youth director is undervalued, which sometimes undermines his passion for this work.

Instead of paying our staff just enough, or doing so without a clear sense of transparency or taking into account past performance, I would simply reinforce Ton’s recommendation to pay them a bit more than enough. If we practice this approach consistently and regularly, in time the culture in our field will shift. We will save funds and resources while experiencing lower turnover, increased efficiency and productivity, and revenue growth. It happened for Costco; it can happen for us.

Yes, this requires up-front investment, and an understanding from donors, patrons, and foundations what is truly the cost of doing our work in a way that will lead to ultimate and sustainable success.

ADJUSTING PRACTICES TO ACHIEVE EQUITY:

We have thirteen narratives in this book, seven women and six men. Seven are now in an executive or #1 position, as both Graham and Laura move CEO or Head of School roles respectively after my Fall 2017 interview with them. Four of the seven executives are women. I intended to profile a diverse breadth of Jewish community professionals, yet these numbers are not truly representative of our larger field, in which the workforce predominantly is approximately 70% women yet the leadership of our organizations, especially legacy institutions, is approximately 70% men. In The Forward survey of CEO salaries in 2017, only two women were in the top 30, and they held positions #29 and #30.

Similarly, according to both Pew and Leading Places to Work, the gender pay gap in the Jewish world merely mirrors global society. Those who identify as women were paid $.79 to every $1 man were paid as of 2019. So, clearly, the gap in leadership roles and pay isn’t unique to the Jewish community, but today’s Jewish community professionals are still cursed with this reality.

During my time as the Managing Director of the Leadership Commons at the William Davidson School of JTS, the Leadership Commons conducted a research initiative that examined how we and various collaborators could advance women into more leadership positions and reduce the gender pay gap in Jewish Education. Our initial thoughts were to provide more training to women to give them the tools and skills to navigate hiring committees and salary negotiations. We quickly understood, however, that this was the wrong strategy. Thanks to the leadership of two extraordinary academics and project directors, JTS Faculty Dr. Shira Epstein, now Dean of the William Davidson School, and Project Director Dr. Andrea Jacobs, we reexamined our models to ask what we expect of our executives, regardless of gender.

We have an expectation that leadership must always come from the top and must always work 24 hours a day 7 days week (many times working by attending social functions during the Sabbath as well) in order to be “successful.” This model also includes posting a laundry list of expectations and functions in the job-descriptions we see on jewishjobs.com or on the websites of executive firms. These jobs are often untenable for anyone committed to be a present parent, a responsibility we still largely place on women.

Our model of negotiating also fails to work properly. We put the onus on the candidate to advocate for themselves for the highest salary possible instead of offering our best offer from the start to their desired candidate which, on its own as a solution, would reduce the gender pay gap. This is coupled with living in a society where it is ok for men to be aggressive, to negotiate and be tough, and still today, for women might be called “difficult” when they act identically.

In light of today’s societal changes and in reflecting the experiences of the profiles we have just seen, we have ample data to help change the models of leadership with respect to gender. In doing so, all of today’s Jewish community professionals could then feel that they are playing on level playing field, and thus be more enthused to be part of a Jewish community who lives up to these values. We can get there by adjusting our practices and regularly practicing the following:

- Returning to compensation – be transparent. Stop negotiating. Set a salary level, not even a range, that is impressive for the role, non-negotiable, and identical regardless of the new hire’s gender. Follow the guidance from the Talmud (Bava Metzia 83b) to “raise our worker’s wages in order for them to do better work.”

- Re-writing the job description – We must not write job descriptions that look like a laundry list of obligations. Let us be realistic with the job functions and expectations of our executives and all of our employees so they can do better work and have a meaningful life with family or other interests and friends beyond work.

- Training hiring committees – In the 2019 Gender Equity and Leadership Initiative report released by the Leadership Commons, Epstein and Jacobs advocate for training hiring committees through a gender lens. We need to put our biases out in the open and have someone on our committees say out loud, “are we saying this about this person because of their gender? Let’s be honest with ourselves.” Further, JTS’s Seeds of Innovation program, which provided seed money for JTS alumni to create an innovative project that supports the Jewish community, granted JTS alumnae Dr. Sara Shapiro Plevan and Rabbi Rebecca Sirbu, funds to launch a hiring committee training program which can train a “gender lens ambassador” on every executive hiring committee – which every organization reading would benefit from participating in.

In considering her legacy, Aliza from Blessing #6 shared with me a frustration she’s had for most of her professional life: finding female role models in the Jewish sector who are also executives. Aliza laments that it is not a long list. While she hopes she can be such a role model for others by the end of her career, she hopes she doesn’t reach that point without having to find such a role model for herself. She wants to be celebrated within a network of other change makers and other women leaders who helped change the face of what leadership looks like in the Jewish community.

Aliza’s concerns resonated with many of our female portraits, notably Becky and Carine, as well as several of the male-identifying individuals we profiled. Our field is predominately female, yet the vast majority of executives especially at legacy institutions are male, and this hasn’t changed much over the past two generations as more females have entered the work force and obtained graduate degrees. This, sadly, has sent a clear message to females that they, other than occasionally, will not be welcomed and accepted as executives in our field. As we consider the consequence of Blessing #6 when we allow many of our Jewish community professionals to feel “ostracized” or “othered,” the current emerging generation of Jewish community professional leadership has, like Aliza, much less patience for this reality.

ADJUST OUR APPROACH TO WORK LIFE BALANCE

The story of creation in the book of Genesis is a story that gave us the most precious gift of Jewish tradition, Shabbat. On Shabbat we have the space to commit to three actions: to rest, reflect, and express gratitude. Shabbat can lead to a happier life because we regain our energy learn from our reflections and feel more appreciative of our lives. Consider our week, or our work, to be like a symphony. In playing a page of sheet music, there are notes and there are rests. The music only works well when the performers rest at the right times, makes the notes they do play clear, ordered, crisp and compelling.

Jewish community professionals must be allowed to have a similar approach. Alyson, for example, has the rest time to be with her family. As a result, she is a stronger Jewish educator, performing with excellence when she is playing the notes of her job. Carine can set her own schedule so she can give herself the time off when she needs it. Those professionals who can have true time off, both during their work and doing their year, are able to rest, reflect, and express gratitude, and play their work notes with gusto.

A new trend in promoting work/life balance is the Sabbatical – which more and more executives are taking, not just clergy. The Jim Joseph Foundation is currently exploring how to support for organizations and employees at multiple levels to take a significant Sabbatical. We can think of the Sabbatical – etymologically related to “Shabbat” – as a way to take time off in order to recharge and feel blessed for what we have and have accomplished.

We already know empirically and anecdotally that today’s Jewish community professionals work hard, and they shouldn’t feel as if they need to work all the time in order to get the work done. Here are simple steps we can take to help bless our Jewish professionals in the area of balance:

- Review job descriptions and responsibilities with them – are we asking for too much? Allow the professional to have input into the formation and balance of their own job.

- Review their work hours – do they make sense given the work they need to complete? Perhaps it is possible they can navigate their responsibilities in a modified schedule that works for them and still satisfies the organization.

- Review a staff person’s needs – Perhaps a great worker needs time during a weekday for family or different work hours given their current commute time.

- As we explored in Blessing #9, consider with the professional how they can bring more of their personal interests and integrated self to their work. In addition to rest, the professional may find more balance if they find more of their full selves in the workplace.

By being aware of employees’ needs, they will already feel a sense of value, motivation, and blessing. This again speaks to our Jewish professionals today simply needing to feel heard, visible, and validated. This shouldn’t be the exception in our field; it must standard operating practice.

CONCLUSION: Just as amplifying what we do well will help better bless our workforce and help us get out of the vicious cycle and onto the virtuous cycle, so will making the necessary adjustments. The idea of blessing is nothing new in the area of Jewish tradition. To conclude our journey together, let’s go back to our original source, the Torah and a story from my own journey that has led to this project to Bless Our Workforce, Mah Tovu.